Overview of the Lesson

The first part of this lesson dives into natural language processing (NLP), using the IMDB movie review dataset. We train a classifier that categorises if a review is negative or positive. This is called sentiment analysis. This is done via a state-of-the-art NLP algorithm called ULMFiT.

Next the lesson shows how to use deep learning with tabular data using fastai.

Lastly the lesson shows how collaborative filtering models (aka recommender systems) can be built using similar ideas to those for tabular data, but with some special tricks to get both higher accuracy and more informative model interpretation.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

- We want to build a NLP classifier.

- Task: IMDB movie reviews - postive or negative?

- Using neural networks for NLP classification hasn’t been successful until a break through made in 2018 – ULMFit. This is what FastAI is using now.

- Just as we have seen already in imaging problems, we can get good performance by using transfer learning.

- In NLP transfer learning means taking a language model which has be pretrained on some large corpus of text and then fine tuning that for our current problem using its own text corpus.

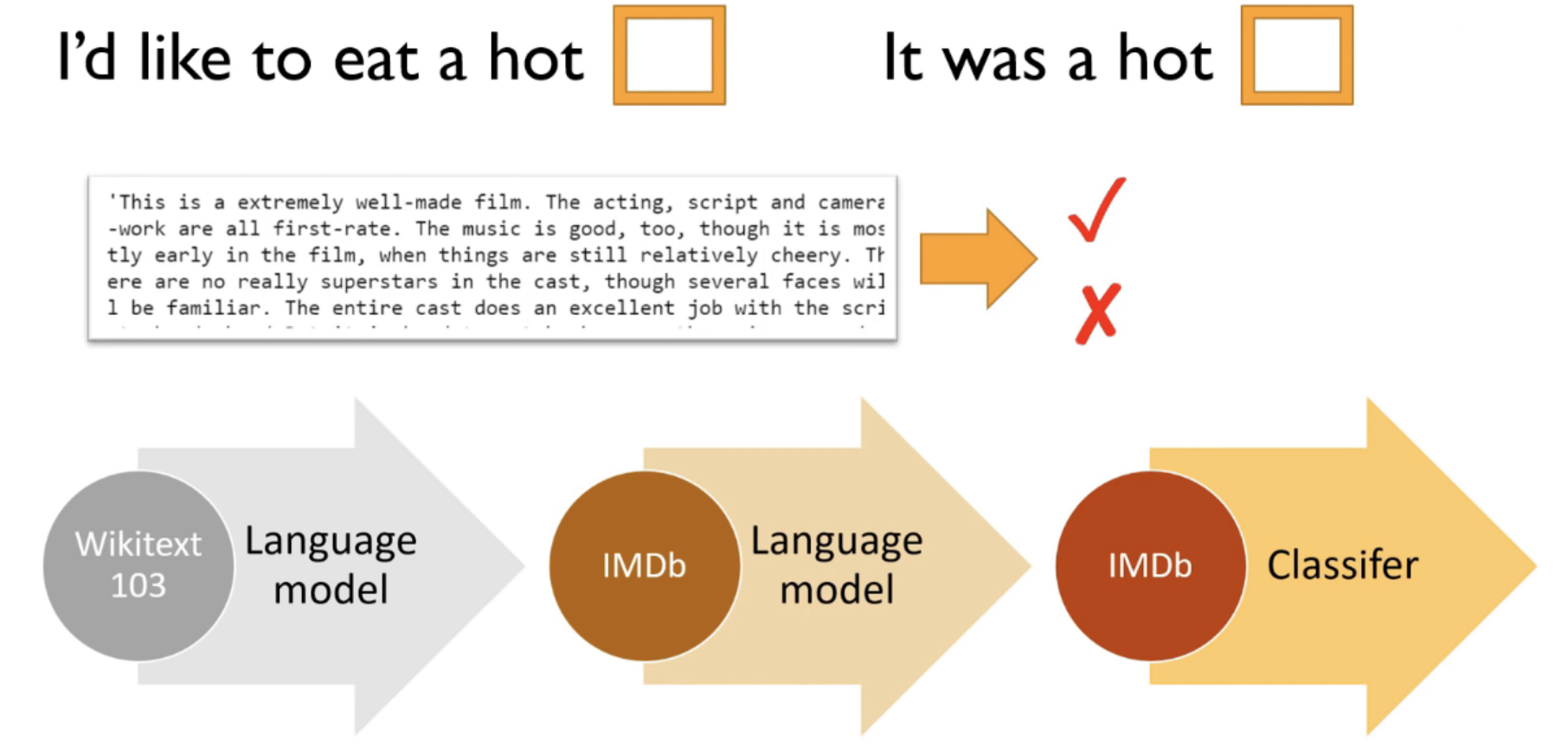

Language Model

- The language model in this case is a special type of neural network called an RNN (recurrent neural network) and what it does is predict the next word given a sequence of prior words. So in the diagram above you have the sentences:

- “I’d like to eat a hot [ ]” : the language model should predict “dog”

- “It was a hot [ ]” : the language model should predict “day”

- This takes 2-3 days to train on a decent GPU, so not much point in you doing it. You may as well start with ours. Even if you’ve got a big corpus of like medical documents or legal documents, you should still start with Wikitext 103. There’s just no reason to start with random weights. It’s always good to use transfer learning if you can.

- Once you have trained your language model you can stick it on the internet (e.g. github) for others to download and use for their own NLP problems. fastai provides a pretrain language model trained on text from Wikipedia.

- This kind of learning is what Yann Lecun calls “Self-supervised Learning”. You don’t give the dataset labels, rather the labels are built into the data itself.

Fine Tuning the Language Model

-

Starting from the pretrained Wikitext language model you can fine tune the language model with your own target corpus. Every domain that you work in will have its own domain specific language that it uses.

- For the case of movie reviews it may learn about actor’s names or certain vocabulary will be more important. For example:

- “My favourite actor is Tom ___ (Cruise)”

- “I thought the photography was fantastic but I wasn’t really so happy about the _____ (director).”

- Fine tuning your language model will take a long time. However this is basically a one-time cost. You only have to train the language model once and then you can use that model for training classifiers or whatever, which won’t take a long time to train.

- This transfer learning approach works very well and gives state of the art performance on the IMDB dataset.

IMDB Sentiment Classification

The data loading process for text was covered in the previous lesson. Here is a short review:

- Load data using a data bunch or the data block API

- The data is tokenized: this means that text is split into raw words or ‘tokens’. Special tokens denote puncuation, unknown words etc.

- The tokenized data is then numericalized: every token is assigned its own unique number. A text document becomes a list of numbers, which can be processed by a neural network.

This data loading and transforming is achieved in fastai with the data block API:

data = (TextList.from_csv(path, 'texts.csv', cols='text')

.split_from_df(col=2)

.label_from_df(cols=0)

.databunch())

Training the Language Model

No point training the Wikitext 103 model from scratch just download the pretrained one from fastai. Instead we want to start with that a fine tune it with the IMDB corpus. First we load the IMDB data for language model learning:

bs=48

data_lm = (TextList.from_folder(path)

#Inputs: all the text files in path

.filter_by_folder(include=['train', 'test', 'unsup'])

#We may have other temp folders that contain text files so we only keep what's in train and test

.split_by_rand_pct(0.1)

#We randomly split and keep 10% (10,000 reviews) for validation

.label_for_lm()

#We want to do a language model so we label accordingly

.databunch(bs=bs))

data_lm.save('data_lm.pkl')

We can say:

- It’s a list of text files﹣the full IMDB actually is not in a CSV. Each document is a separate text file.

- Say where it is﹣in this case we have to make sure we just to include the

trainandtestfolders. - We randomly split it by 0.1.

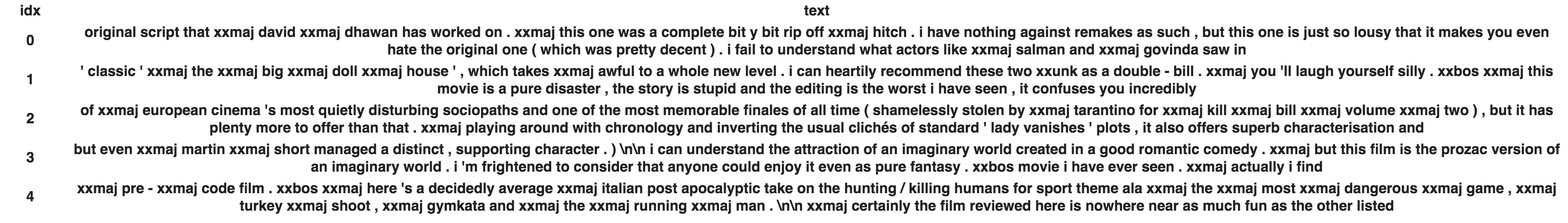

This data looks like:

You then train the language model, not using a CNN rather a Recursive Neural Network (RNN). In fastai the code is:

learn = language_model_learner(data_lm, AWD_LSTM, drop_mult=0.3)

The pretrained language model that comes from fastai is AWD_LSTM: link.

You then do usual routine for training:

- Run LRFind

- Train the network head (1-2 epochs)

- Unfreeze

- Run LRFind again

- Train the whole network (5+ epochs).

- Save the encoder:

learn.save_encoder('fine_tuned_enc')

Predicting Text with the Language Model

With the trained language model we can have some fun by making it finish sentences.

TEXT = "I liked this movie because"

N_WORDS = 40

N_SENTENCES = 2

print("\n".join(learn.predict(TEXT, N_WORDS, temperature=0.75) for _ in range(N_SENTENCES)))

The output of this:

I liked this movie because of the cool scenery and the high level of xxmaj british hunting . xxmaj the only thing this movie has going for it is the horrible acting and no script . xxmaj the movie was a big disappointment . xxmaj I liked this movie because it was one of the few movies that made me laugh so hard i did n’t like it . xxmaj it was a hilarious film and it was very entertaining . xxmaj the acting was great , i ‘m

Text Classifier

Load the data:

data_clas = (TextList.from_folder(path, vocab=data_lm.vocab)

#grab all the text files in path

.split_by_folder(valid='test')

#split by train and valid folder (that only keeps 'train' and 'test' so no need to filter)

.label_from_folder(classes=['neg', 'pos'])

#label them all with their folders

.databunch(bs=bs))

Create a text classifer and give it the language model we trained:

learn = text_classifier_learner(data_clas, AWD_LSTM, drop_mult=0.5)

learn.load_encoder('fine_tuned_enc') # load language model

Tabular Data

Tabular data is one of the most common problems that data scientists work on day-to-day. This are things like spreadsheets, relational databases, or financial reports. People used to be sceptical about using neural networks for tabular data - everybody knows you should be using XGBoost! However not only does it work well, it can do things that even XGBoost can’t do.

fastai has created the module fastai.tabular for using NNs with tabular data.

Loading the Data

Import the fastai modules:

from fastai import *

from fastai.tabular import *

The data input is assumed to be a pandas dataframe. Here is the Adult dataset, which is a classic dataset where you have to predict somebody’s salary given a number of variables like age, education, occupation etc:

path = untar_data(URLs.ADULT_SAMPLE)

df = pd.read_csv(path/'adult.csv')

For fastai’s tabular models you need to tell it about your columns:

- Which column is the target variable?

- Which columns have continuous variables?

- Which columns have categorical variables?

- What preprocessing do you want to do to the columns?

In code these variables look like:

dep_var = 'salary'

cat_names = ['workclass', 'education', 'marital-status', 'occupation', 'relationship', 'race']

cont_names = ['age', 'fnlwgt', 'education-num']

procs = [FillMissing, Categorify, Normalize]

Using these we can then load the data using data block API:

data = (TabularList.from_df(df, path=path, cat_names=cat_names,

cont_names=cont_names, procs=procs)

.split_by_idx(list(range(800,1000)))

.label_from_df(cols=dep_var)

.add_test(test, label=0)

.databunch())

There are a number of processors in the fastai library. The ones we’re going to use this time are:

FillMissing: Look for missing values and deal with them some way (e.g. mean, median…).Categorify: Find categorical variables and turn them into Pandas categoriesNormalize: Do a normalization ahead of time which is to take continuous variables and subtract their mean and divide by their standard deviation so they are zero-one variables.

For the full list of transforms available see the documentation.

Training the Model

learn = tabular_learner(data, layers=[200,100], metrics=accuracy)

learn.fit(1, 1e-2)

Total time: 00:03

epoch train_loss valid_loss accuracy

1 0.362837 0.413169 0.785000 (00:03)

This creates a tabular_learner network with the parameter layers=[200, 100]. What is this exactly? If you look at model in pytorch, learn.model:

TabularModel(

(embeds): ModuleList(

(0): Embedding(10, 6)

(1): Embedding(17, 8)

(2): Embedding(8, 5)

(3): Embedding(16, 8)

(4): Embedding(7, 5)

(5): Embedding(6, 4)

(6): Embedding(3, 3)

)

(emb_drop): Dropout(p=0.0)

(bn_cont): BatchNorm1d(3, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(layers): Sequential(

(0): Linear(in_features=42, out_features=200, bias=True)

(1): ReLU(inplace)

(2): BatchNorm1d(200, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(3): Linear(in_features=200, out_features=100, bias=True)

(4): ReLU(inplace)

(5): BatchNorm1d(100, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(6): Linear(in_features=100, out_features=2, bias=True)

)

)

The tabular learner is a just a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) (the layers group) with some funny input bolted onto the front of it. In the layers group you can see the first two Linear layers have an output size of 200 and 100, respectively. These are the sizes we put into the layers parameter in the model. So it’s a two layer MLP with layer sizes of 200 and 100.

The input layer consists of a bunch of Embedding layers. We’ll explain these later, but basically for each of the categorical features in the data (there are 6 here) there is an embedding layer. An embedding maps the total number of unique values of a categorical variable to a lower dimensional continuous vector space. If you take the zeroth embedding layer as an example:

(0): Embedding(10, 6)

This variable has 9 unique values + 1 null value added by the fastai processors. Its output is 6 dimensional.

All of the outputs of the embedding layers are concatenated together along with the 3 continuous features to create a 42 dimensional vector that is the input to the MLP part of the network.

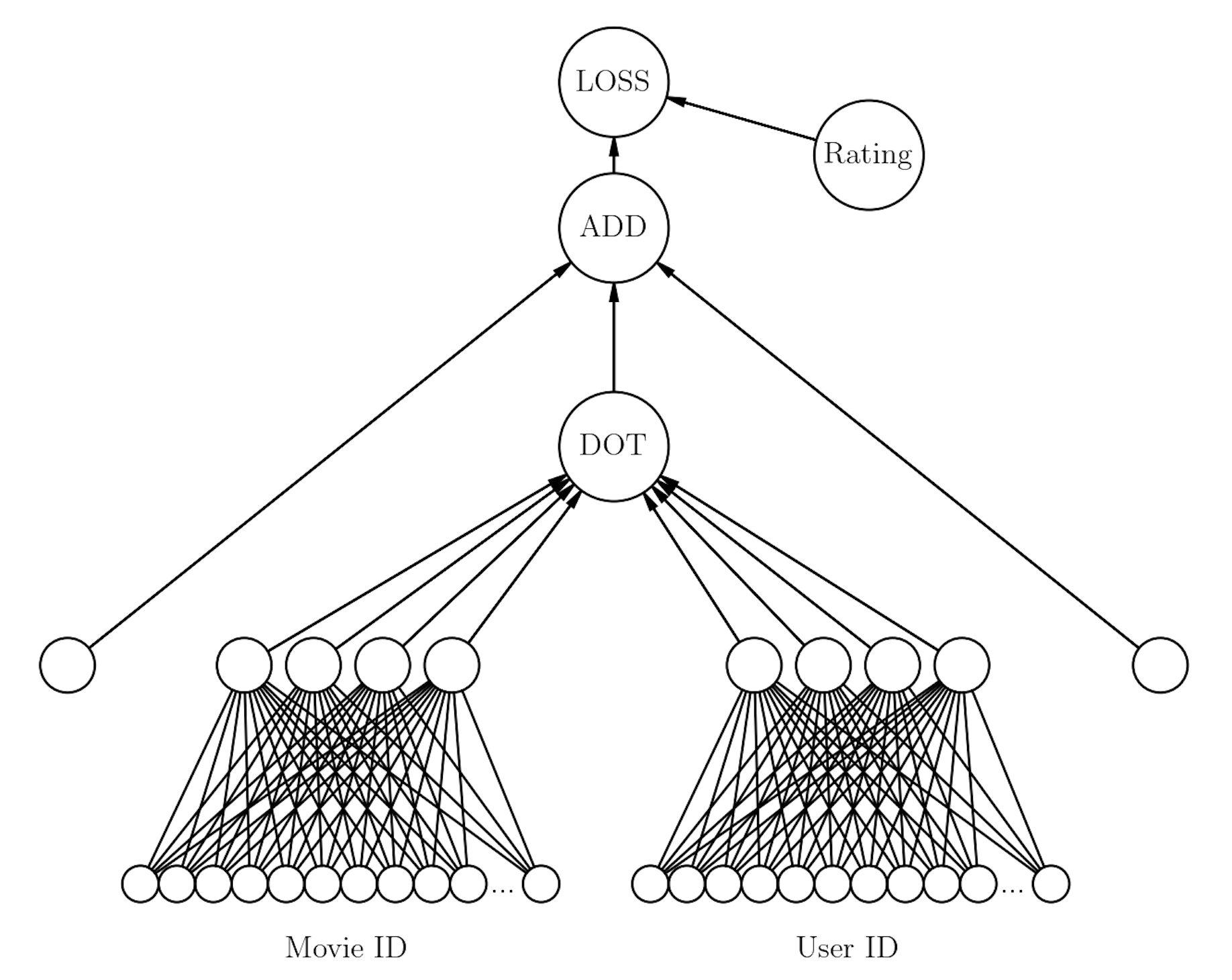

Collaborative Filtering

Collaborative filtering is where you have many users and many items and you want to predict how much a certain user is going to like a certain item. You have historical information about who bought what, who liked which item etc. You then want to predict what a particular user would like that they haven’t seen before.

The most basic version would be a table with userId, movieId, and rating:

| userId | movieId | rating | timestamp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 73 | 1097 | 4.0 | 1255504951 |

| 1 | 561 | 924 | 3.5 | 1172695223 |

| 2 | 157 | 260 | 3.5 | 1291598691 |

| 3 | 358 | 1210 | 5.0 | 957481884 |

| 4 | 130 | 316 | 2.0 | 1138999234 |

The data is sparse - no single user has rated even a decent fraction of the films and many films haven’t been rated.

To achieve these aims, the problem is posed as a Matrix Factorisation problem. That is you suppose that there is some matrix that describes all the users $U$, and a matrix that describes all the movies $M$, and that the ratings of all the movies by all the users is the matrix product of these two matrices: \(UM = R\) The matrices $U$ and $M$ are called the Embedding matrices. The idea is that every row of the matrix $U$ is some $D_u$ dimensional vector that represents a single user, and likewise every row of the matrix $M$ is some $D_m$ dimensional vector that represents a single movie. These vectors are such that, if I take the dot product of a user vector and movie vector it will predict the rating the user would assign that movie.

The embeddings here are the same as what we saw earlier in the categorical variables for tabular data. It’s worth taking a deeper dive into what these are.

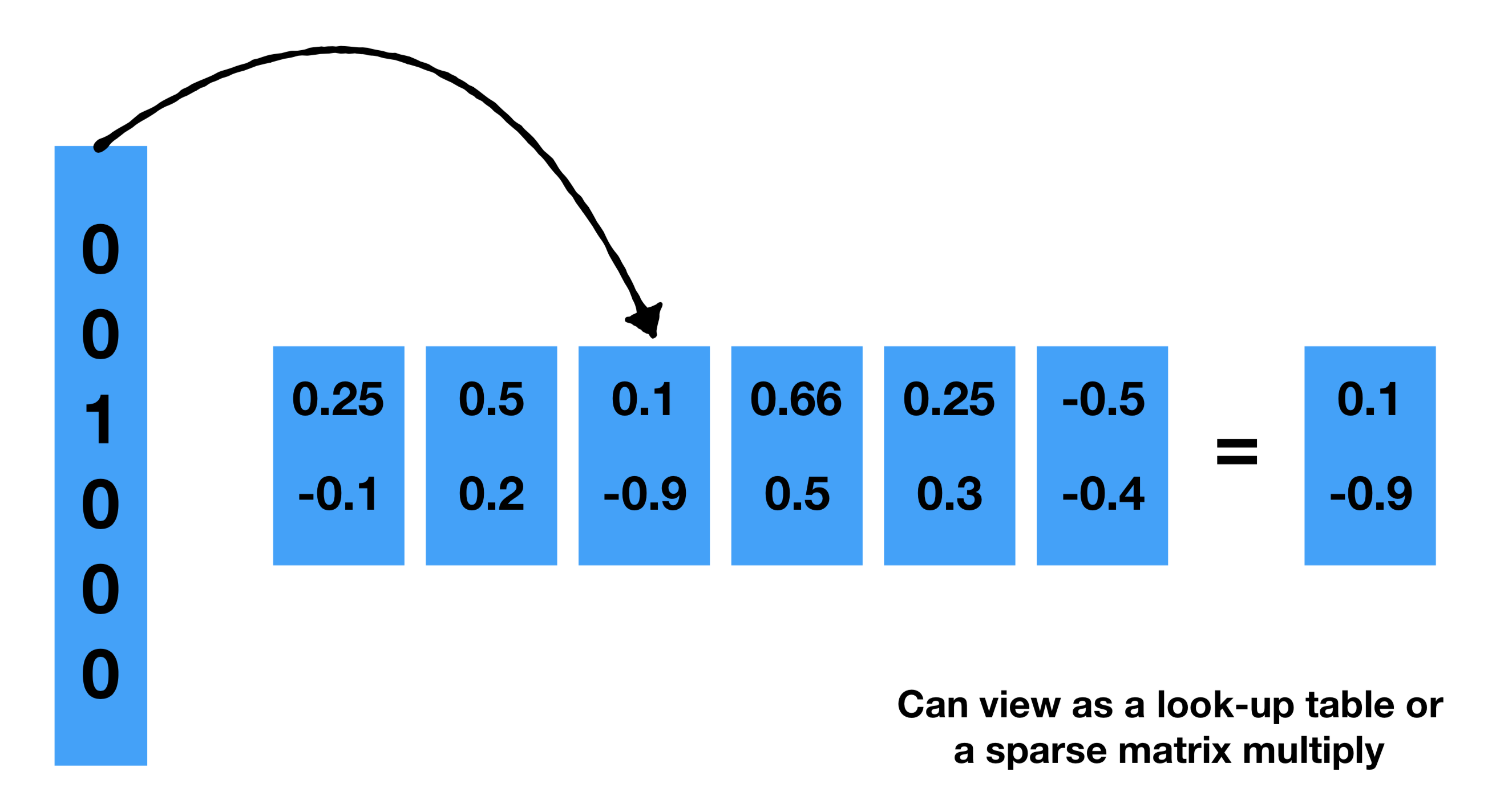

Embeddings

-

Given that users and movies are only categorical variables, how do we determine how ‘far apart’ they are from each other. How similar is one film to another. How similar is one user to another?

-

Often in machine learning categorical variables are represented using One-hot Encoding.

-

This is where categorical variables are represented as a sparse vector, with a dimension for every unique value. For example, consider three items:

'Twix': [1, 0, 0] 'Kit-kat': [0, 1, 0] 'Vodka': [0, 0, 1] -

This is often sufficient for categorical variables in machine learning algorithms. However there is a lack of meaning in these vectors. For example, all the vectors are equidistant, but I know that ‘Twix’ and ‘Kit-kat’ are both chocolate bars and so are ‘nearer’ to each other than they are to ‘Vodka’. One-hot encoding does not encode these semantics.

-

This is what embeddings can do for us. An embedding is a matrix of weights. They map these one-hot vectors to a continuous vector space that encodes some meaning about the categories. In the example above this could be some 2D space of ‘foody’ things and ‘drinky’ things:

'Twix': [0.98, 0] 'Kit-kat': [0.97, 0] 'Vodka': [0.1, 0.95] -

But the meaning is context dependent. The embedded space dimensions could represent anything like whether the item is expensive or whether it is more likely to be consumed at night.

-

Embeddings have to be trained with supervised learning. They are initialized with random weights and then learned in collaborative filtering and in the tabular network with gradient-descent.

Embedding Layer as a Look-up Table

What does an embedding layer look like under the hood? text mining - How does Keras ‘Embedding’ layer work? - Cross Validated

- It’s pretty much a lookup table of vectors. You have an input size of 5000 and an embedding size of 100 then you will have a list of 5000 100d vectors. You could represent this as a spare-vector dense matrix multiply, but that would be inefficient.

Embedding Layer as matrix multiplication

The lookup, multiplication, and addition procedure we’ve just described is equivalent to matrix multiplication. Given a $1 \times N$ sparse representation $S$ and an $N \times M$ embedding table $E$, the matrix multiplication $S \times E$ gives you the $1 \times M$ dense vector.

Different Uses of Embeddings

- Embeddings map items (e.g. movies, text…) to a low dimensional dense eal vectors such that similar items are close to each other.

- Embeddings can also be applied to dense data (e.g. audio) to create a meaningful similarity metric.

- Jointly embedding diverse data types (e.g. text, images, audio…) can define a similarity metric between them.

Example: Movie Lens Dataset

Link to notebook here.

First you choose some number of factors $N_f$. This is the size of the embedding. There are $N_u$ users and $N_m$ movies. You then create emedding matrices for users and movies:

- User embedding matrix of size $(N_u, N_f)$

- Movie embedding matrix of size $(N_m, N_f)$

Note that the sizes of the embeddings for the users and movies, $N_f$, have to be the same because we are taking a dot product of them.

You can also add biases. Maybe some users just really like movies a lot more than other users. Maybe there are certain movies that everybody just likes. So in addition to the matrices you can add a single movie for how much a user likes movies, and a single number for how popular a movie is.

So the prediction of how a user would rate a movie would be the dot product of the vector from the user embedding matrix with the vector from the movie embedding matrix, plus the bias for the user and the bias for the movie. This intuitively makes sense - you have the embedded model of how users like different movies (embedding model), and then the individual characteristics of that particular user and that particular film (bias).

The rating of the movie is then calculated using a sigmoid function with a range of 0 to 5 stars.

In fastai the code to do this is:

ratings = pd.read_csv(path/'ratings.csv')

data = CollabDataBunch.from_df(ratings, seed=42)

y_range = [0,5.5]

learn = collab_learner(data, n_factors=50, y_range=y_range)

learn.fit_one_cycle(3, 5e-3)

What does the model look like?

$> learn.model

EmbeddingDotBias(

(u_weight): Embedding(101, 50)

(i_weight): Embedding(101, 50)

(u_bias): Embedding(101, 1)

(i_bias): Embedding(101, 1)

)

In this dataset there are 100 movies and 100 users. The inputs to the embedding layers are of size 101. This is because fastai adds in a ‘null’ category. You can see this in the CollabDataBunch object:

$> data.train_ds.x.classes

OrderedDict([('userId',

array(['#na#', '15', '17', '19', ..., '652', '654', '664', '665'], dtype='<U21')),

('movieId',

array(['#na#', '1', '10', '32', ..., '6539', '7153', '8961', '58559'], dtype='<U21'))])

#na#

Cold Start Problem

If you don’t have any data on your user’s preferences then you can’t recommend them anything. There isn’t an easy solution to this; likely the only way is to have a second model which is not a collaborative filtering model but a metadata driven model for new users or new movies. A few possible approaches to tackle this problem:

- Ask the user in the UX. For example Netflix proposes films and tv series to a user and asks them which ones they like so that it can bootstrap collaborative filtering.

- You could use metadata about the user and the products and handcraft a crude recommendation system that way.

Jeremy Says…

- If you’re doing NLP stuff, make sure you use all of the text you have (including unlabeled validation set) to train your language model, because there’s no reason not to. In Kaggle competions they don’t give you the labels for the test set, but you can still use the test data for self-supervised learning. Lesson 4: A little NLP trick

- Jeremy used to use random forests / xgboost with tabular data 99% of the time. Today he uses neural networks 90% of the time. It’s his goto method he tries first.

Q & A

-

Does the language model approach works for text in forums that are informal English, misspelled words or slangs or shortforms like s6 instead of Samsung S 6? [12:47]

Yes, absolutely it does. Particularly if you start with your wikitext model and then fine-tune it with your “target” corpus. Corpus is just a bunch of documents (emails, tweets, medical reports, or whatever). You could fine-tune it so it can learn a bit about the specifics of the slang , abbreviations, or whatever that didn’t appear in the full corpus. So interestingly, this is one of the big things that people were surprised about when we did this research last year. People thought that learning from something like Wikipedia wouldn’t be that helpful because it’s not that representative of how people tend to write. But it turns out it’s extremely helpful because there’s a much a difference between Wikipedia and random words than there is between like Wikipedia and reddit. So it kind of gets you 99% of the way there.

So language models themselves can be quite powerful. For example there was a blog post from SwiftKey (the folks that do the mobile-phone predictive text keyboard) and they describe how they kind of rewrote their underlying model to use neural nets. This was a year or two ago. Now most phone keyboards seem to do this. You’ll be typing away on your mobile phone, and in the prediction there will be something telling you what word you might want next. So that’s a language model in your phone.

Another example was the researcher Andrej Karpathy who now runs all this stuff at Tesla, back when he was a PhD student, he created a language model of text in LaTeX documents and created these automatic generation of LaTeX documents that then became these automatically generated papers. That’s pretty cute.

We’re not really that interested in the output of the language model ourselves. We’re just interested in it because it’s helpful with this process.

-

How to combine NLP (tokenized) data with meta data (tabular data) with Fastai? For instance, for IMBb classification, how to use information like who the actors are, year made, genre, etc. [49:14]

Yeah, we’re not quite up to that yet. So we need to learn a little bit more about how neural net architectures work as well. But conceptually, it’s kind of the same as the way we combine categorical variables and continuous variables. Basically in the neural network, you can have two different sets of inputs merging together into some layer. It could go into an early layer or into a later layer, it kind of depends. If it’s like text and an image and some metadata, you probably want the text going into an RNN, the image going into a CNN, the metadata going into some kind of tabular model like this. And then you’d have them basically all concatenated together, and then go through some fully connected layers and train them end to end. We will probably largely get into that in part two. In fact we might entirely get into that in part two. I’m not sure if we have time to cover it in part one. But conceptually, it’s a fairly simple extension of what we’ll be learning in the next three weeks.

-

Where does the magic number of

in the learning rate come from? [33:38]

learn.fit_one_cycle(2, slice(1e-3/(2.6**4),1e-3), moms=(0.8,0.7))Good question. So the learning rate is various things divided by 2.6 to the fourth. The reason it’s to the fourth, you will learn about at the end of today. So let’s focus on the 2.6. Why 2.6? Basically, as we’re going to see in more detail later today, this number, the difference between the bottom of the slice and the top of the slice is basically what’s the difference between how quickly the lowest layer of the model learns versus the highest layer of the model learns. So this is called discriminative learning rates. So really the question is as you go from layer to layer, how much do I decrease the learning rate by? And we found out that for NLP RNNs, the answer is 2.6.

How do we find out that it’s 2.6? I ran lots and lots of different models using lots of different sets of hyper parameters of various types (dropout, learning rates, and discriminative learning rate and so forth), and then I created something called a random forest which is a kind of model where I attempted to predict how accurate my NLP classifier would be based on the hyper parameters. And then I used random forest interpretation methods to basically figure out what the optimal parameter settings were, and I found out that the answer for this number was 2.6. So that’s actually not something I’ve published or I don’t think I’ve even talked about it before, so there’s a new piece of information. Actually, a few months after I did this, Stephen Merity and somebody else did publish a paper describing a similar approach, so the basic idea may be out there already.

Some of that idea comes from a researcher named Frank Hutter and one of his collaborators. They did some interesting work showing how you can use random forests to actually find optimal hyperparameters.

-

How does the language model trained in this manner perform on code switched data (Hindi written in English words), or text with a lot of emojis?:

Text with emojis, it’ll be fine. There’s not many emojis in Wikipedia and where they are at Wikipedia it’s more like a Wikipedia page about the emoji rather than the emoji being used in a sensible place. But you can (and should) do this language model fine-tuning where you take a corpus of text where people are using emojis in usual ways, and so you fine-tune the Wikitext language model to your reddit or Twitter or whatever language model. And there aren’t that many emojis if you think about it. There are hundreds of thousands of possible words that people can be using, but a small number of possible emojis. So it’ll very quickly learn how those emojis are being used. So that’s a piece of cake.

I’m not really familiar with Hindi, but I’ll take an example I’m very familiar with which is Mandarin. In Mandarin, you could have a model that’s trained with Chinese characters. There are about five or six thousand Chinese characters in common use, but there’s also a romanization of those characters called pinyin. It’s a bit tricky because although there’s a nearly direct mapping from the character to the pinyin (I mean there is a direct mapping but that pronunciations are not exactly direct), there isn’t direct mapping from the pinyin to the character because one pinyin corresponds to multiple characters.

So the first thing to note is that if you’re going to use this approach for Chinese, you would need to start with a Chinese language model.

Actually fastai has something called Language Model Zoo where we’re adding more and more language models for different languages, and also increasingly for different domain areas like English medical texts or even language models for things other than NLP like genome sequences, molecular data, musical MIDI notes, and so forth. So you would you obviously start there.

To then convert that (in either simplified or traditional Chinese) into pinyin, you could either map the vocab directly, or as you’ll learn, these multi-layer models﹣it’s only the first layer that basically converts the tokens into a set of vectors, you can actually throw that away and fine-tune just the first layer of the model. So that second part is going to require a few more weeks of learning before you exactly understand how to do that and so forth, but if this is something you’re interested in doing, we can talk about it on the forum because it’s a nice test of understanding.

-

Regarding using NN for Tabular data: What are the 10% of cases where you would not default to neural nets? [40:41]:

Good question. I guess I still tend to give them a try. But yeah, I don’t know. It’s kind of like as you do things for a while, you start to get a sense of the areas where things don’t quite work as well. I have to think about that during the week. I don’t think I have a rule of thumb. But I would say, you may as well try both. I would say try a random forest and try a neural net. They’re both pretty quick and easy to run, and see how it looks. If they’re roughly similar, I might dig into each and see if I can make them better. But if the random forest is doing way better, I’d probably just stick with that. Use whatever works.

-

Do you think that things like

scikit-learnandxgboostwill eventually become outdated? Will everyone will use deep learning tools in the future? Except for maybe small datasets?[50:36]I have no idea. I’m not good at making predictions. I’m not a machine learning model. I mean

xgboostis a really nice piece of software. There’s quite a few really nice pieces of software for gradient boosting in particular. Actually, random forests in particular has some really nice features for interpretation which I’m sure we’ll find similar versions for neural nets, but they don’t necessarily exist yet. So I don’t know. For now, they’re both useful tools.scikit-learnis a library that’s often used for pre-processing and running models. Again, it’s hard to predict where things will end up. In some ways, it’s more focused on some older approaches to modeling, but I don’t know. They keep on adding new things, so we’ll see. I keep trying to incorporate more scikit-learn stuff into fastai and then I keep finding ways I think I can do it better and I throw it away again, so that’s why there’s still no scikit-learn dependencies in fastai. I keep finding other ways to do stuff. -

What about time series on tabular data? is there any RNN model involved in

tabular.models? [1:05:09]:We’re going to look at time series tabular data next week, but the short answer is generally speaking you don’t use a RNN for time series tabular data but instead, you extract a bunch of columns for things like day of week, is it a weekend, is it a holiday, was the store open, stuff like that. It turns out that adding those extra columns which you can do somewhat automatically basically gives you state-of-the-art results. There are some good uses of RNNs for time series, but not really for these kind of tabular style time series (like retail store logistics databases, etc).

Links and References

- Lesson video: https://course.fast.ai/videos/?lesson=4

- Homework notebooks:

- Notebook 1: lesson4-collab.ipynb

- Notebook 2: lesson4-tabular.ipynb

- Parts of my notes have been copied from the excellent lecture transcriptions made by @hiromi. Link: Lesson4 Detailed Notes.

- Link to ULMFiT paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.06146

- Fastai blog post on tabular data An Introduction to Deep Learning for Tabular Data · fast.ai

- Medium post on recommenders with NN: Collaborative Embeddings for Lipstick Recommendations

- Lecture on Embeddings: Embeddings, Machine Learning Crash Course, Google Developers

- Word2Vec: Vector Representations of Words

- Paper Review: Neural Collaborative Filtering Explanation & Implementation

- Blog post from Twitter on Embeddings: Embeddings@Twitter

- Video: Embeddings for Everything: Search in the Neural Network Era

- Applying the four step “Embed, Encode, Attend, Predict” framework to predict document similarity

- Mini-course on Recommendation Systems, Google: Introduction to Recommendation Systems, Google Developers